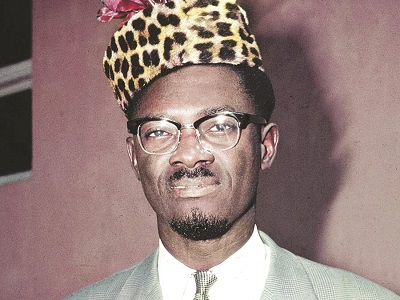

Patrice Lumumba was assassinated sixty years ago this month – on 17 January 1961. He is worth remembering, for since his cruel murder, his country, the Congo Democratic Republic (CDR) has never known real peace. Its troubles are a constant reminder to Africa that imperialism will stop at nothing to cripple an African country, if the African nation’s independence threatens the “interests” of imperialist powers who have their eyes on its natural resources.

Lumumba (1925-1961) was – next to Nelson Mandela – the iconic figure who most readily comes to mind when Africa is discussed in relation to its struggle against imperialism and racism.

Mandela suffered tremendously. But he won.

Lumumba, on the other hand, lost – he lost power, he lost his country, and in the end, he lost his life. All were forcibly taken from him by a combination of forces that was probably the most powerful ever deployed against a single individual in history.

The amazing thing is that Lumumba had done absolutely nothing against those who wanted his blood. They just saw him as a threat to their interests; interests narrowly defined to mean, ‘His country has got resources. We want them. He might not give them to us. So let us go kill him.’

I insist, though, that he should not be seen only as a victim of forces too powerful for him to contend with. On the contrary, he should be seen as someone who fully recognised the power of the forces ranged against him and fought valiantly with every ounce of breath in his body, and with great intelligence, to try and save his country.

Lumumba tried to get the United Nations to save his country from the Belgians. The UN did send a “peace-keeping force to the Congo. But instead of assisting the Lumumba Government that had invited it to the country, the UN force worked against it.

Thus, we can see in the history of the African people’s struggle in the 20th century, Mandela and Lumumba representing the two ends of the pole that swung within the axis that marked the fulcrum of that struggle. The two men represent the beacon of light that shines sharply to bring absolute clarity into the evaluation of a history that is often mired in obfuscation and mendacity.

To those who say, ‘How wonderful it was to see in Mandela, the issue of oppression so peacefully resolved’, we need only point to that picture of Patrice Lumumba, a torturer’s hand in his hair, as he was brutalised while driving in a truck by black Kantangese soldiers at Elizabethville (now Kisangani).

In that picture of Lumumba, serious students can espy unseen hands, steered by a ‘heart of darkness’, bribing, mixing poisons, assembling rifles with telescopic sights, and finally propping an elected prime minister against a tree in the bush and riddling his body with bullets.

And then – could even Joseph Conrad, author of The Heart of Darkness, in his worst nightmarish ramblings, have imagined this? – first, the Belgians burying Lumumba’s body, then exhuming it a day later because the burial ground was too close to a road, and then hacking it to pieces, and shoving the pieces into a barrel filled with sulphuric acid, to dissolve it?

And could Joseph Conrad have been able to picture one Belgian murderer making sure to break off two front teeth from Lumumba’s jaw, to keep as a “memento” to show off to the grand-children in Brussels in years to come?

That a Belgian could engage in such barbarities against a leader elected on the basis of a constitution signed into law by the hand of his own King (Baudoin the First) is eloquent testimony of the forces that were ranged against Lumumba in 1960-61.

The sordid murder of Lumumba in the Katanga bush near Elizabethville (now Kisangani) 60 years ago was the logical conclusion of a bitter and vigorous campaign that Belgium, aided by the United States, waged in the Congo in to ensure that Patrice Lumumba would never get a chance to rule the country that had elected him to be its leader. Because of the actions of Belgium and the United States, we actually do not know whether Lumumba would have made a good ruler or not. Which makes Lumumba even more important to history: for he was not assassinated merely as a person, but as an idea!

What was that idea? It was the idea of a Congo that was fully independent, non-aligned, and committed to African unity. Lumumba’s party, the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), was the only one in the Congo to organise itself successfully as a party that saw the Congo as one nation, not as a conglomeration of ethnic groups.

The MNC thus gained the largest number (33 out of 1370 OF seats in the Congolese Parliament. From this relatively strong base, Lumumba was able to inspire other Congolese “parties” to join him in trying to realise his vision of one Congo. He hatch alliances with parties whose parochialism he must have despised – so long as such alliance enabled his MNC to command an overall majority of seats in the Congolese Parliament.

When Lumumba was unwillingly appointed Prime Minister by the Belgians, many of the Belgians in the Congo and in Belgium itself thought the heavens had fallen in. For he was not the Belgians’ choice at all! They tried other Congolese ‘leaders’ (such as Joseph Kasavubu) and it was only when these failed to garner adequate support that they were forced to call on Lumumba.

The magnitude of the achievement of the MNC in forcing the Belgians to recognise its supremacy, is not often appreciated by historians, because it is not often realised that the Congo is, in fact, as big in size as all the countries of Western Europe put together!

(As for Belgium itself, it is outrageous that it should have wanted to run the Congo in the first place – the Congo is 905,563 square miles in size, compared to Belgium’s puny 11,780 sq. miles. In other words, Belgium had arrogated to itself the task of ruling a country more than eight times its own size.)

Not only is the Congo huge, but think of a country the size of Western Europe that does not have good roads, railway systems, telecommunications facilities or modern airports. And a Western Europe in which political parties are allowed to be formed only one year before vital elections.

The vital national elections held in 1960 followed local government elections held only a year earlier – in 1959! By one stroke of the pen, the Belgians were to allow ethnic movements to be suddenly transformed into “parties” (The Belgians had hitherto forbidden the formation of national political parties). Now, these regional entities were hurriedly recognised and invited to take part in deciding the Congo’s future national constitutional arrangements.

Would the Congo’s local government elections create a situation whereby – perish the thought – the winners might actually elect Congolese Cabinet Ministers? After 100 years, was there to be an African leader as in Ghana (Kwame Nkrumah) or Guinea (SekouToure) in the Congo too? The Belgians were frightened out of their wits. But they had no choice.

(TO BE CONTINUED)

By CAMERON DUODU