In the waning days of 2019, a new coronavirus was reported to have emerged in the central Chinese city of Wuhan. Reports linked initial clusters of cases to a seafood market (one where many animal species were slaughtered and sold).

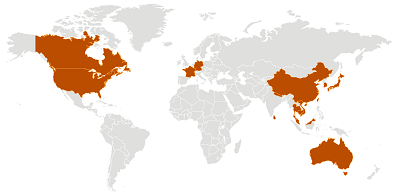

In the subsequent weeks the virus has spread throughout the province, to other parts of China, and now to countries around the world, with cases reported in four of the six regions of the World Health Organization (Western Pacific, Southeast Asia, Americas, and Europe.)

The epidemiologic information about the virus is being developed by teams of researchers around the world, yet as of January 26, we still do not know exactly how infectious the virus is (how many people do we expect one person to infect), we do not have confirmation regarding routes of transmission, its precise severity, nor if any therapeutics are more helpful than others. In the absence of such data, guidance to the public has amounted to:

- Wash your hands,

- Cover your cough,

- Stay away from sick animals or humans,

- Cook meat and eggs thoroughly, and

- Get your flu shot (which is not effective against a coronavirus, but will help keep down the number of potential influenza patients- a disease with very similar symptoms.)

With growing public fear and few other options in terms of protective measures to take, decision-makers have advised against travel to China, and the Chinese government has taken the unprecedented move of limiting the movement of more than 50 million people by ceasing all transportation in and out of major cities. All of this is taking place during the Lunar New Year—a time when typically over 380 million people in China travel to be with family.

This virus, like other highly infectious, serious diseases in a highly mobile population, spreads across geopolitical boundaries and requires multisectoral coordination and collaboration in order to effectively respond and mitigate the consequences of the outbreak. It underscores why global health governance is critical to saving lives.

The International Health Regulations (IHR) is the governing treaty for global preparedness and response to public health emergencies. This agreement has evolved over 150 years with changes in science and technology, with the last major revision coming in 2005, following the emergence and spread of SARS around the world. This treaty guides the declaration of public health emergencies of international concern; provides processes for public health, travel, and trade recommendations during a public health emergency; tasks WHO with coordinating an international response; allows WHO to utilize a multitude of sources to inform their actions; is supposed to prevent nations from taking non-evidence based actions as part of the response (such as closing borders); and requires information sharing and communication during a public health emergency.

It also requires nations to develop core public health infrastructure so that they are able to rapidly detect, assess, and report a public health emergency, as well as mount an initial response.

The IHR also explicitly speaks to the importance of respecting human rights and only curtailing travel and trade when absolutely necessary. These conditions create critical global norms for the member states of the World Health Organization, particularly in light of quarantines and other social distancing measures that have been instituted to control the spread of the disease.

Even beyond the rights provided to the WHO by the 196 parties to the IHR, the organization can be a beacon of information, promoting and eventually approving new countermeasures, providing ethical standards for the response, and sharing best practices for clinical care during an outbreak.

Yet, the organization is not sufficiently resourced to sustain response activities, particularly in light of other public health emergencies around the world, including an Ebola outbreak that continues to ravage the conflict-prone northeast region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Over the coming weeks, WHO will be responsible for making a determination as to whether the emerging outbreak constitutes a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and providing evidence-based recommendations regarding travel, clinical care, and any non-pharmaceutical measures.

The WHO needs to become the trusted and timely source of verified epidemiologic information, pushing any reticent county to take productive response actions and managing the use of any experimental medical countermeasures.

This outbreak will test the WHO, but it will also underscore the importance of strong global governance of disease in the face of an infectious respiratory disease spreading around the world. In the immediate future, we must ensure WHO has all the tools it requires to manage this outbreak.

Over time, we will need to investigate how to strengthen the tools for global governance and ensure that the systems we have in place are fit for purpose in an evolving world.

By Rebecca Katzand Alexandra L. Phelan